An old friend stopped by the other day, having heard through his colleague, who heard from my Gay Old Soulmate, of my diagnosis. I don’t think we have seen each other since my Gay Old Soulmate and I went down to the Schuylkill to watch him in the dragon boat races four years ago, and I, with my poor eyesight, strained in vain to figure out which figure in which boat was he. He commented that in earlier times we would hardly go three days without seeing one another. That was a different lifetime for us both.

An old friend stopped by the other day, having heard through his colleague, who heard from my Gay Old Soulmate, of my diagnosis. I don’t think we have seen each other since my Gay Old Soulmate and I went down to the Schuylkill to watch him in the dragon boat races four years ago, and I, with my poor eyesight, strained in vain to figure out which figure in which boat was he. He commented that in earlier times we would hardly go three days without seeing one another. That was a different lifetime for us both.

A doctor, he asked the medical questions about staging and Gleason scores and mentioned some other numbers that I didn’t understand. It felt as though he knew more about my prognosis from my limp attempt to describe what the surgeon had told us than I did myself—which felt comforting. It recalled the time he saved my life. Fifteen or sixteen years ago. I waited for a liver transplant. One night I began bleeding internally. Blissfully ignorant, I knew only that I had not the strength to get up from the bathroom floor. My Gay Old Soulmate called him in desperation, and he came in the middle of the night. I presume he grasped the critical nature of my condition when he saw me. But I insisted they take me to a hospital across town where I knew the doctors. He advised calling the ambulance. He told me he would let me ride across town if I could make it down the stairs on my own energy. I could only go, sitting butt down, stair by stair, one step at a time. That settled it. He called 911, conveying the urgency to the operator with a host of medical terms I did not fully comprehend and now do not remember. I remember only that the ambulance came and I made it to the emergency room on time.

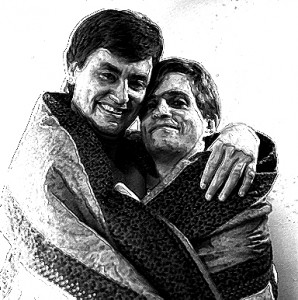

Now we primarily see each other on Facebook, or at times of crisis like this. It feels good to see him settled on the sofa again. We pick up with news of each other’s lives, his partner’s Ph.D. defense, my recent retirement and our celebratory trip to Phoenix to visit his ex—and cancer. The intertwining of our lives no longer brings us face to face with any frequency. But our lives remain connected. Even over the years and chasm of experience that caused our worlds to diverge, we are bound together.

We no longer promise, as we once did, “I’ll call you,” or say, “We should get together more often.” We know we won’t. Without fail, another diagnosis, another dragon boat race, or . . . . We will see each other again.